Health Care for Feral Cats

The overall health and life expectancy of feral cats

Those opposed to TNR programs claim outdoor cats are suffering, diseased, and living a life of extreme misery. No doubt there are some unmanaged groups in unhealthy condition, but more often the cats we see in managed groups are hardy survivors and very healthy. A New Zealand study published in 2019 assessed the health of pet cats, managed, and unmanaged colony cats and found “that stray cats–particularly managed stray cats–can have reasonable welfare that is potentially comparable to companion cats,” (Zito et al.). Additionally, an Israeli study showed that male outdoor cats that are neutered tend to be healthier than those that are in tact, most likely due to weaker territorial and aggressive behavior (Gunther et al., 2018).

In 2019, Alley Cat Rescue surveyed rescue organizations across the United States that provide TNR services to their communities, and out of the 218 groups that responded, 72% reported the average age of outdoor group cats to be around 2 - 6 years old. Another 20% said the feral cats they assist are between 6 and 10 years old. 25% of the groups responded that the oldest cats in their groups were 13 years or older.

Feline viral diseases

The major feline viral diseases are feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). These viruses are specific to cats and cannot be transmitted to humans or other animals.

Large epidemiologic studies “indicate FeLV and FIV are present in approximately 4% of feral cats, which is not substantially different from the infection rate reported for pet cats” (Levy and Crawford, 2004).

Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP)

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a viral disease caused by certain strains of the feline coronavirus. Infected cats usually show no symptoms in the initial stages of coronavirus infection, and the virus only progresses into clinical FIP in a small number of infected cats - five to 10 percent — and only when there is a mutation of the virus or an abnormality in the immune response (Cornell, “Feline Infectious Peritonitis," 2014).

Because the symptoms of FIP are not uniform, often manifesting differently in different cats, and sometimes appearing similar to other diseases, there is no definitive way to diagnose it without a biopsy. Veterinarians often diagnose based on an evaluation of the cat’s history and symptoms in combination with coronavirus test results (Cornell, “Feline Infectious Peritonitis,” 2014).

Although a recently developed anti-viral drug called GS-441524 (GS) has been shown to be able to cure a majority of FIP infections, its use is not practical for many feral cats as it must be administered by injection daily over a period of at least 12 weeks. The cost of the drug varies greatly between manufacturers, but is a minimally $80 per 5 mL bottle, which is beyond the means of many rescues and caretakers. However, those with the ability and resources to treat a feral cat or kitten with GS have a good chance of saving that animal’s life.

For more detailed information about FIP, visit saveacat.org/fip-felv-fiv.html

Feline leukemia virus (FeLV)

The feline leukemia virus (FeLV) is a cancer-causing virus. In addition to causing feline leukemia, FeLV suppresses the cat’s immune system, leaving the animal vulnerable to a variety of opportunistic diseases.

The signs and symptoms of infection with FeLV are varied and include loss of appetite, poor coat condition, infections of the skin, bladder and respiratory tract, oral disease, seizures, swollen lymph nodes, fatigue, fever, weight loss, recurring bacterial and viral illnesses, anemia, diarrhea, and jaundice (Cornell, “Feline Leukemia Virus,” 2014). Some cats can be carriers of the disease yet show no signs of illness for many years.

Infected cats shed FeLV primarily in their saliva, although the virus may also be present in the blood, tears, feces, or urine. Other modes of FeLV transmission include mutual grooming, sharing food dishes and litter boxes, and in utero transfer from a mother cat to her kittens. A mother cat can also transmit FeLV to her kittens through infected milk.

There is no cure for FeLV, although good supportive care can improve the quality of an infected cat’s life. Nutritional support (herbs, vitamins) and other alternative treatments can help strengthen a cat’s impaired immune system.

Most TNR programs choose not to test feral cats for the disease. Whether a feral cat tests negative for the disease or she is not tested, we strongly recommend all feral cats receive a FeLV vaccine to reduce the risk of transmission.

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is a retrovirus that virologists classify as a lentivirus, or "slow-acting virus" (Cornell, “Feline Immunodeficiency Virus,” 2014). FIV suppresses a cat’s immune system, compromising her ability to fight off infection. However, diagnosed with FIV may live long, healthy lives, never showing symptoms of the virus, though some cats may experience “recurrent illness interspersed with periods of relative health” (Cornell, “Feline Immunodeficiency Virus,” 2014).

Common signs and symptoms of the disease include poor coat condition; persistent fever; loss of appetite; weight loss; inflammation of the gums and mouth; chronic or recurrent skin, urinary tract, bladder, and upper respiratory infections; and a variety of eye conditions may occur.

Fortunately, FIV is not transmitted easily. The primary mode of transmission is through bite wounds. This explains why the cats most likely to become infected are free-roaming, unneutered males prone to territorial fighting. FIV does not spread through casual contact among cats, so it is possible to keep an FIV-infected cat in the same house as a healthy cat with little risk of transmission, provided the cats tolerate each other and do not fight.

There is a vaccine to protect against FIV, though it is rarely administered. Any cat who receives the vaccine will then test positive for the disease, because she will be carrying antibodies.

There is no cure for FIV; however, veterinarians can treat or at least alleviate the infections associated with the virus. Proper nutrition and good supportive care can help strengthen a cat’s impaired immune system and improve her quality of life.

To test or not to test?

Testing for viral diseases such as FeLV and FIV in feral cat groups should be optional and not mandatory. Funds for TNR programs are usually limited, so resources may be better spent on sterilization and rabies vaccines rather than on testing. Alley Cat Rescue does not perform testing as part of our standard TNR program; however, all cats who are placed into our adoption program or feral cats who are relocated are tested.

Operation Catnip’s founder, Dr. Julie Levy, points out that the greatest cause of feline deaths in the United States is the killing ー by humans ー of unwanted stray and feral cats, which causes more deaths than all feline infectious diseases combined (Levy and Crawford, 2004). Subsequently, most TNR programs choose to focus their efforts and resources on sterilization and vaccination rather than testing.

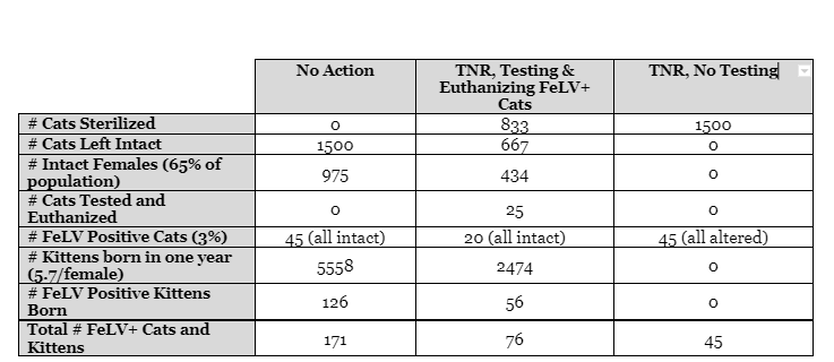

The occurrence and rate of transmission for FeLV and FIV in feral cats is very low. FeLV is primarily spread from infected mother cats to their kittens, and FIV is mostly spread among fighting tomcats through deep bite wounds. Therefore, spaying and neutering will decrease these activities and the spread of these infections. As shown in the chart below, courtesy of Dr. Julie Levy, applying all resources to TNR rather than split between testing for FeLV/removing FeLV + cats and TNR typically results in fewer FeLV+ cats in a colony after one year (45 vs. 76 cats).

Those opposed to TNR programs claim outdoor cats are suffering, diseased, and living a life of extreme misery. No doubt there are some unmanaged groups in unhealthy condition, but more often the cats we see in managed groups are hardy survivors and very healthy. A New Zealand study published in 2019 assessed the health of pet cats, managed, and unmanaged colony cats and found “that stray cats–particularly managed stray cats–can have reasonable welfare that is potentially comparable to companion cats,” (Zito et al.). Additionally, an Israeli study showed that male outdoor cats that are neutered tend to be healthier than those that are in tact, most likely due to weaker territorial and aggressive behavior (Gunther et al., 2018).

In 2019, Alley Cat Rescue surveyed rescue organizations across the United States that provide TNR services to their communities, and out of the 218 groups that responded, 72% reported the average age of outdoor group cats to be around 2 - 6 years old. Another 20% said the feral cats they assist are between 6 and 10 years old. 25% of the groups responded that the oldest cats in their groups were 13 years or older.

Feline viral diseases

The major feline viral diseases are feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). These viruses are specific to cats and cannot be transmitted to humans or other animals.

Large epidemiologic studies “indicate FeLV and FIV are present in approximately 4% of feral cats, which is not substantially different from the infection rate reported for pet cats” (Levy and Crawford, 2004).

Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP)

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a viral disease caused by certain strains of the feline coronavirus. Infected cats usually show no symptoms in the initial stages of coronavirus infection, and the virus only progresses into clinical FIP in a small number of infected cats - five to 10 percent — and only when there is a mutation of the virus or an abnormality in the immune response (Cornell, “Feline Infectious Peritonitis," 2014).

Because the symptoms of FIP are not uniform, often manifesting differently in different cats, and sometimes appearing similar to other diseases, there is no definitive way to diagnose it without a biopsy. Veterinarians often diagnose based on an evaluation of the cat’s history and symptoms in combination with coronavirus test results (Cornell, “Feline Infectious Peritonitis,” 2014).

Although a recently developed anti-viral drug called GS-441524 (GS) has been shown to be able to cure a majority of FIP infections, its use is not practical for many feral cats as it must be administered by injection daily over a period of at least 12 weeks. The cost of the drug varies greatly between manufacturers, but is a minimally $80 per 5 mL bottle, which is beyond the means of many rescues and caretakers. However, those with the ability and resources to treat a feral cat or kitten with GS have a good chance of saving that animal’s life.

For more detailed information about FIP, visit saveacat.org/fip-felv-fiv.html

Feline leukemia virus (FeLV)

The feline leukemia virus (FeLV) is a cancer-causing virus. In addition to causing feline leukemia, FeLV suppresses the cat’s immune system, leaving the animal vulnerable to a variety of opportunistic diseases.

The signs and symptoms of infection with FeLV are varied and include loss of appetite, poor coat condition, infections of the skin, bladder and respiratory tract, oral disease, seizures, swollen lymph nodes, fatigue, fever, weight loss, recurring bacterial and viral illnesses, anemia, diarrhea, and jaundice (Cornell, “Feline Leukemia Virus,” 2014). Some cats can be carriers of the disease yet show no signs of illness for many years.

Infected cats shed FeLV primarily in their saliva, although the virus may also be present in the blood, tears, feces, or urine. Other modes of FeLV transmission include mutual grooming, sharing food dishes and litter boxes, and in utero transfer from a mother cat to her kittens. A mother cat can also transmit FeLV to her kittens through infected milk.

There is no cure for FeLV, although good supportive care can improve the quality of an infected cat’s life. Nutritional support (herbs, vitamins) and other alternative treatments can help strengthen a cat’s impaired immune system.

Most TNR programs choose not to test feral cats for the disease. Whether a feral cat tests negative for the disease or she is not tested, we strongly recommend all feral cats receive a FeLV vaccine to reduce the risk of transmission.

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is a retrovirus that virologists classify as a lentivirus, or "slow-acting virus" (Cornell, “Feline Immunodeficiency Virus,” 2014). FIV suppresses a cat’s immune system, compromising her ability to fight off infection. However, diagnosed with FIV may live long, healthy lives, never showing symptoms of the virus, though some cats may experience “recurrent illness interspersed with periods of relative health” (Cornell, “Feline Immunodeficiency Virus,” 2014).

Common signs and symptoms of the disease include poor coat condition; persistent fever; loss of appetite; weight loss; inflammation of the gums and mouth; chronic or recurrent skin, urinary tract, bladder, and upper respiratory infections; and a variety of eye conditions may occur.

Fortunately, FIV is not transmitted easily. The primary mode of transmission is through bite wounds. This explains why the cats most likely to become infected are free-roaming, unneutered males prone to territorial fighting. FIV does not spread through casual contact among cats, so it is possible to keep an FIV-infected cat in the same house as a healthy cat with little risk of transmission, provided the cats tolerate each other and do not fight.

There is a vaccine to protect against FIV, though it is rarely administered. Any cat who receives the vaccine will then test positive for the disease, because she will be carrying antibodies.

There is no cure for FIV; however, veterinarians can treat or at least alleviate the infections associated with the virus. Proper nutrition and good supportive care can help strengthen a cat’s impaired immune system and improve her quality of life.

To test or not to test?

Testing for viral diseases such as FeLV and FIV in feral cat groups should be optional and not mandatory. Funds for TNR programs are usually limited, so resources may be better spent on sterilization and rabies vaccines rather than on testing. Alley Cat Rescue does not perform testing as part of our standard TNR program; however, all cats who are placed into our adoption program or feral cats who are relocated are tested.

Operation Catnip’s founder, Dr. Julie Levy, points out that the greatest cause of feline deaths in the United States is the killing ー by humans ー of unwanted stray and feral cats, which causes more deaths than all feline infectious diseases combined (Levy and Crawford, 2004). Subsequently, most TNR programs choose to focus their efforts and resources on sterilization and vaccination rather than testing.

The occurrence and rate of transmission for FeLV and FIV in feral cats is very low. FeLV is primarily spread from infected mother cats to their kittens, and FIV is mostly spread among fighting tomcats through deep bite wounds. Therefore, spaying and neutering will decrease these activities and the spread of these infections. As shown in the chart below, courtesy of Dr. Julie Levy, applying all resources to TNR rather than split between testing for FeLV/removing FeLV + cats and TNR typically results in fewer FeLV+ cats in a colony after one year (45 vs. 76 cats).

Effect of Test and Removal on FeLV Prevalence

There is no reliable test for FIP, which is mainly found in catteries and crowded shelters and is less likely to occur in feral cat colonies. Also, mass screenings of healthy cats can result in large numbers of false positives. All cats testing positive should be retested to properly confirm diagnosis, which is usually not possible in the case of feral cats, due to limited resources.

Vaccination protocols for feral cats

Typically, feral cats receive vaccinations at the time of sterilization; however, cats can be re-trapped later to update any vaccines.

Due to the rabies virus being a zoonotic disease, meaning it can be transmitted to humans, most health codes and laws require that all cats receive a rabies vaccination. Kittens can receive a rabies vaccine as early as 12 weeks of age.

ACR strongly recommends providing a three-year rabies vaccination to adequately protect adult feral cats for at least three years, and possibly even longer. In our experience, we have found that five- to even year-old feral cats, who are part of managed groups, are easier to retrap, as opposed to retrapping the cats every year. The cats will know and trust the caretaker and can be more easily trapped. Cats who are trapped too often may become trap-shy, making retrapping much more difficult.

Second in importance to a rabies vaccine, all feral cats should receive an FVRCP vaccine, providing funding allows. This is a combination vaccine that includes protection against rhinotracheitis, calici, Chlamydia psittaci, and feline distemper.

The risk of vaccine-induced sarcoma, a highly malignant cancer, has caused the veterinary community to look into the possibility that cats have been over-vaccinated. In 1996, the Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force (VAFSTF) formed to investigate how to prevent these sarcomas. The panel made new vaccination recommendations that booster doses of vaccines against feline panleukopenia, feline viral rhinotracheitis and feline calicivirus (FVRCP) now only be administered every three years instead of the traditional one-year booster. The panel found that the three-year rabies vaccination provides adequate immunity, and suggested this over the annual shots to lessen the risk of sarcomas forming (American Veterinary Medical Association, 2001).

Additional health concerns for feral cats

During spay/neuter surgery, the veterinarian will examine the cat’s skin for wounds or injuries, making sure to thoroughly clean and treat accordingly. A long-acting antibiotic injection, such as Convenia, is usually administered for post-care of sterilization procedures, and will also aid in reducing and treating any infection. For severe wounds or injuries, caretakers can administer additional antibiotics in wet food, or if the veterinary hospital or the caretaker has the space and is capable of housing the cat, she may spend a few days recovering confined to a cage.

Parasite infestations are the most common transmittable health concern for feral cats (Levy and Crawford, 2004). These include internal parasites such as worms, and external parasites such as fleas, ticks, and ear mites. It is highly recommended that TNR programs include treatments to prevent internal and external parasite infestations. Advantage Multi treats a wide range of parasites, so depending on which brand your veterinarian uses, each cat may only need to receive one (monthly) application in order to treat both internal and external parasites. For added protection and to treat severe cases of internal parasites, a topical dewormer such as Profender may also be applied and/or deworming pills and liquids, such as Drontal, can be crushed into wet food. For severe flea infestations, Capstar can be crushed into food and flea powder sprinkled on bedding. Another good option to treat community cats for fleas is food-grade diatomaceous earth. This powder can be sprinkled around the cats' shelters and feeding stations.

Create outdoor litter boxes to give cats a place to go to the bathroom. Scooping frequently will help keep cats healthy and free of contracting the parasite toxoplasmosis, a zoonotic disease that can be transmitted to humans. Providing cats an appropriate place to go to the bathroom will also help alleviate any complaints about cats using gardens and flower beds to relieve themselves.

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) are also common in feral cats, especially kittens. Signs and symptoms of URIs include nasal discharge, eye discharge, sneezing, and wheezing. Loss of appetite is also common in cats with URIs because their sense of smell is decreased due to a stuffy nose. A long-acting antibiotic injection, such as Convenia, can be administered or daily antibiotics, such as Clavamox or Amoxicillin, can be added to wet food for treatment of secondary bacterial infections, which often develop during the viral infection. For cats who can be handled, antibiotic eye ointments can also be administered.

For more detailed information, see Chapter 11 of our Guide to Managing Community Cats

References

-Alley Cat Rescue. Feral Cat Survey. N.p., 2019.

-American Veterinary Medical Association. Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force. N.p., 2001. Web. 18 Aug. 2014.

-Cornell Feline Health Center. “Feline Immunodeficiency Virus.” Ithaca, New York: Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, 2014. http://www.vet.cornell.edu/FHC/health_resources/brochure_fiv.cfm.

-Cornell Feline Health Center. “Feline Leukemia Virus.” Ithaca, New York: Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, 2014. http://www.vet.cornell.edu/FHC/health_resources/brochure_fiv.cfm.

-Gunther, I.; Raz, T.; Klement, E. "Association of neutering with health and welfare of urban free-roaming cat population in Israel, during 2012-2014." Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2018, 157, 26–33.

-Levy, Julie K., and P. Cynda Crawford. “Humane Strategies for Controlling Feral Cat Populations.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 225.9 (2004): 1354–60. Avmajournals.avma.org (Atypon). Web. 18 Aug. 2014.

-Zito, Sarah, et al. “A Preliminary Description of Companion Cat, Managed Stray Cat, and Unmanaged Stray Cat Welfare in Auckland, New Zealand Using a 5-Component Assessment Scale.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science, vol. 6, Frontiers Media SA, Feb. 2019, https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00040.

Vaccination protocols for feral cats

Typically, feral cats receive vaccinations at the time of sterilization; however, cats can be re-trapped later to update any vaccines.

Due to the rabies virus being a zoonotic disease, meaning it can be transmitted to humans, most health codes and laws require that all cats receive a rabies vaccination. Kittens can receive a rabies vaccine as early as 12 weeks of age.

ACR strongly recommends providing a three-year rabies vaccination to adequately protect adult feral cats for at least three years, and possibly even longer. In our experience, we have found that five- to even year-old feral cats, who are part of managed groups, are easier to retrap, as opposed to retrapping the cats every year. The cats will know and trust the caretaker and can be more easily trapped. Cats who are trapped too often may become trap-shy, making retrapping much more difficult.

Second in importance to a rabies vaccine, all feral cats should receive an FVRCP vaccine, providing funding allows. This is a combination vaccine that includes protection against rhinotracheitis, calici, Chlamydia psittaci, and feline distemper.

The risk of vaccine-induced sarcoma, a highly malignant cancer, has caused the veterinary community to look into the possibility that cats have been over-vaccinated. In 1996, the Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force (VAFSTF) formed to investigate how to prevent these sarcomas. The panel made new vaccination recommendations that booster doses of vaccines against feline panleukopenia, feline viral rhinotracheitis and feline calicivirus (FVRCP) now only be administered every three years instead of the traditional one-year booster. The panel found that the three-year rabies vaccination provides adequate immunity, and suggested this over the annual shots to lessen the risk of sarcomas forming (American Veterinary Medical Association, 2001).

Additional health concerns for feral cats

During spay/neuter surgery, the veterinarian will examine the cat’s skin for wounds or injuries, making sure to thoroughly clean and treat accordingly. A long-acting antibiotic injection, such as Convenia, is usually administered for post-care of sterilization procedures, and will also aid in reducing and treating any infection. For severe wounds or injuries, caretakers can administer additional antibiotics in wet food, or if the veterinary hospital or the caretaker has the space and is capable of housing the cat, she may spend a few days recovering confined to a cage.

Parasite infestations are the most common transmittable health concern for feral cats (Levy and Crawford, 2004). These include internal parasites such as worms, and external parasites such as fleas, ticks, and ear mites. It is highly recommended that TNR programs include treatments to prevent internal and external parasite infestations. Advantage Multi treats a wide range of parasites, so depending on which brand your veterinarian uses, each cat may only need to receive one (monthly) application in order to treat both internal and external parasites. For added protection and to treat severe cases of internal parasites, a topical dewormer such as Profender may also be applied and/or deworming pills and liquids, such as Drontal, can be crushed into wet food. For severe flea infestations, Capstar can be crushed into food and flea powder sprinkled on bedding. Another good option to treat community cats for fleas is food-grade diatomaceous earth. This powder can be sprinkled around the cats' shelters and feeding stations.

Create outdoor litter boxes to give cats a place to go to the bathroom. Scooping frequently will help keep cats healthy and free of contracting the parasite toxoplasmosis, a zoonotic disease that can be transmitted to humans. Providing cats an appropriate place to go to the bathroom will also help alleviate any complaints about cats using gardens and flower beds to relieve themselves.

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) are also common in feral cats, especially kittens. Signs and symptoms of URIs include nasal discharge, eye discharge, sneezing, and wheezing. Loss of appetite is also common in cats with URIs because their sense of smell is decreased due to a stuffy nose. A long-acting antibiotic injection, such as Convenia, can be administered or daily antibiotics, such as Clavamox or Amoxicillin, can be added to wet food for treatment of secondary bacterial infections, which often develop during the viral infection. For cats who can be handled, antibiotic eye ointments can also be administered.

For more detailed information, see Chapter 11 of our Guide to Managing Community Cats

References

-Alley Cat Rescue. Feral Cat Survey. N.p., 2019.

-American Veterinary Medical Association. Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force. N.p., 2001. Web. 18 Aug. 2014.

-Cornell Feline Health Center. “Feline Immunodeficiency Virus.” Ithaca, New York: Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, 2014. http://www.vet.cornell.edu/FHC/health_resources/brochure_fiv.cfm.

-Cornell Feline Health Center. “Feline Leukemia Virus.” Ithaca, New York: Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, 2014. http://www.vet.cornell.edu/FHC/health_resources/brochure_fiv.cfm.

-Gunther, I.; Raz, T.; Klement, E. "Association of neutering with health and welfare of urban free-roaming cat population in Israel, during 2012-2014." Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2018, 157, 26–33.

-Levy, Julie K., and P. Cynda Crawford. “Humane Strategies for Controlling Feral Cat Populations.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 225.9 (2004): 1354–60. Avmajournals.avma.org (Atypon). Web. 18 Aug. 2014.

-Zito, Sarah, et al. “A Preliminary Description of Companion Cat, Managed Stray Cat, and Unmanaged Stray Cat Welfare in Auckland, New Zealand Using a 5-Component Assessment Scale.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science, vol. 6, Frontiers Media SA, Feb. 2019, https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00040.